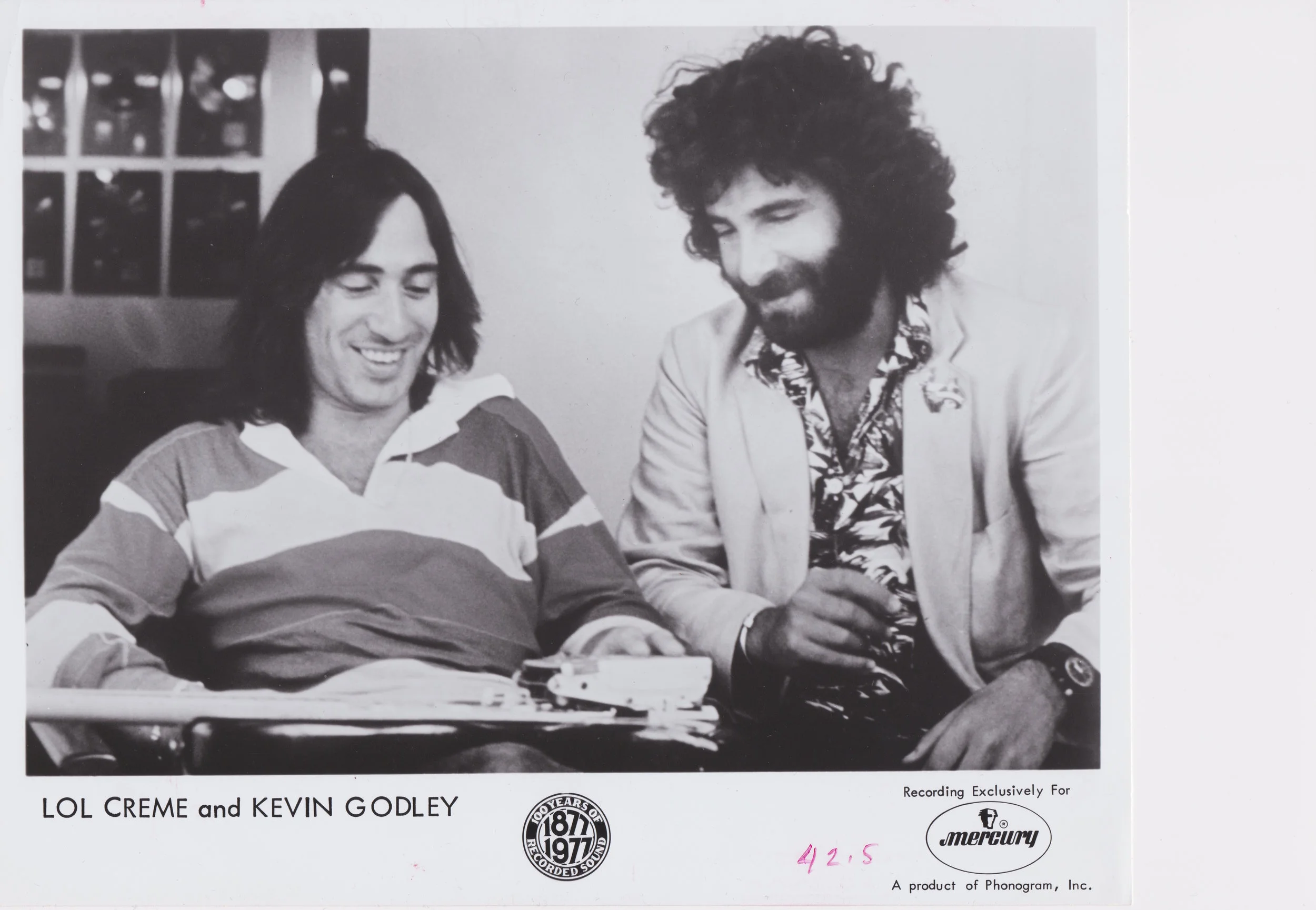

Kevin Godley Discusses Godley & Creme, 10cc, Classic Video Work, and New Projects

Kevin Godley’s ground-breaking work in the areas of music and video is as recognizable as it is brilliant. His influential recordings and video direction comprise an ever-growing body of work that has now been celebrated for decades, even if many of the people around the globe who continue to see, hear, and enjoy his creations may be relatively unfamiliar with the artist behind them. Remarkably -- despite bona fide radio hits to his credit (10cc’s “Not in Love” as well as Godley and Creme’s” Under Your Thumb”, “Wedding Bells”, and “Cry”) and video collaborations with some of the biggest names in pop history -- Godley’s uniquely compelling work is anything but mainstream fare. On the contrary, while Kevin Godley’s recordings, videos, and art can appropriately be experienced within the context of modern pop culture, his creative output in 10cc, Godley & Creme, and on his own somehow also manage to embody the experimental zeitgeist through their bold exploration and sheer ingenuity. Indeed, Kevin Godley’s creations are some of the most enduring, endearing, and inspiring we’ve ever encountered.

Imagine our profound gratitude and excitement, then, when we were recently able to speak at length with Kevin Godley about his illustrious life-long career in the arts -- covering 10cc, Godley & Creme, his iconic and pioneering work within the realm of music videos, the Gizmotron (which he invented with long-time collaborator Lol Creme) and much more. And while his historic body of work would give him every right to rest on his proverbial laurels, Kevin Godley is as productive as ever in 2019, working on new music, game development, and even a full-length film, as he graciously shared with us in the following in-depth conversation.

Bobby Weirdo: Going back to the early days of your music career, you were the drummer in 10cc. Looking back at all the work you’ve done since then with music, video, and art, it’s interesting that part of your identity is in fact as a drummer, and I wanted to touch on that. Stylistically, it sounds like your drumming might have a connection to soul or rhythm and blues.

Kevin Godley: That’s an interesting starting point. When I was a kid, everybody in my group of people wanted to be a musician. Initially, I started out as a guitar player, and I was really shitty. Then I tried to play bass on a guitar, and I was even shittier.

A neighbor of mine had a rich dad who bought him a drum kit. He was a really shitty drummer who didn’t have a sense of rhythm. He had a lovely white Premier drum kit that was wasted on him, and I used to go over there every now and then because I was fascinated by the drums and he let me try to play them.

I quickly discovered that I was ten times better than he was even without having a single lesson -- I just had that independent suspension thing that one has to have, where you have four limbs doing slightly different things. That was my point of no return – I gave up the guitar and got the drums. I loved being able to sit at the back of various local bands and with bands that came through Manchester, and play. I never had a lesson – I just listened to lots and lots of records and picked stuff up. Like most things that I did, I learned by initially copying, and that turned into the way that I play.

I never thought of it as a particular style, and there was no contrivance to make it into a style because I always felt that the drums weren’t a solo instrument. They were part of an overall musical experience, therefore they have their place in the kaleidoscope of sounds. I was always a background person; I was part of the sound. I always tried to blend into what the big picture was trying to be.

When I was at college, I was hugely into Motown, Stax, and soul music, and I guess some of that might have seeped into the way I play. It was just a natural extension of my wanting to do something musically, and finding that the drums was the only thing that I could really do. I found out that I could sing a bit around then, but early on I never wanted to particularly -- it was more about drums.

BW: So you were drumming in early projects, and when you joined 10cc, were you primarily interested in having the role of drummer, or did you know by then that you were interested in other avenues of expression as well?

KG: It’s interesting, because many years before 10cc existed, Lol Creme and I were neighbors. We lived at opposite ends of the same street, and we collaborated on all sorts of mad [things]. We were art students essentially, and good friends. Lol studied in Birmingham, and I studied at Stoke-on-Trent. We used to get together on weekends and hatch plots for musicals and stage shows, write songs, and do design, which we were studying. We didn’t think like everybody else, but that was our joy and what drove us.

So by the time 10cc came into being, we’d already been in the band with Eric Stewart called Hotlegs. We’d had a hit record and had been working at Strawberry Studios as session musicians and as in-house producers. We’d learned our way around the process by the time 10cc came into being, so it was a natural move.

But thinking back on how it all came to be, like most people when they start writing or making music, you’re trying to copy the people you like. It’s impossible not to, because that defines to you what good music is. So we were trying to sound like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and people who we thought were great. But during the process of maturing from copying to exploring, something happens and you become yourself. You stop trying to copy, because something else materializes. And that’s what happened when 10cc formed – we were all at that point where things were beginning to sound unlike anything else that was going on.

It was a gradual process; it wasn’t [a case] where suddenly we were in a band. The people in the band were either friends of ours or we were working with them already – it’s just that the moment when we decided to be a band eluded us for a few years, and then it just clicked.

BW: From the external perspective of a 10cc fan, it looks as if there were -- generally speaking-- two songwriting teams in the band: there was the classic pop team of Eric Stewart and Graham Gouldman, and then there was the more experimental team of Kevin Godley and Lol Creme. And even though the Godley/Creme material was possibly more adventurous, both teams had singles and significant material on those albums. I’m curious about how you experienced the juxtaposition of the pop team with the art team in the same band.

KG: Well, initially it wasn’t obvious, to be honest with you. Looking back on it now, it is, and everybody always mentions that. Initially it was four guys who came from different musical backgrounds: two of which came from a traditional songwriting background -- albeit in a band -- and the other two who came from an art school aesthetic. But we were so enamored with the fact that we had access to our own studio time, and the fact that we were all trying to outdo each other, [though] not in a competitive way.

We had an unconscious desire to create something that was better than what we were listening to on the radio, so the focus was always on the music. We were all – in our own way – doing something to reach that impossible point. The exciting part was when one of us, two of us, or three of us had written something, and we got to play it in its raw form to everybody else. Nine times out of ten it was like, “What the fuck is that? I don’t know, but let’s try recording it and see what we can turn it into.”

So we all were very appreciative of each other’s capabilities, and that’s how we treated it. It was only later that it became increasingly obvious that we were pulling in one direction and they were pulling in another. But nonetheless, we still managed to use what attributes we had to create something magical.

I think there was a chemistry at work – sometimes it’s just that pinch of garlic that you put in a dish that makes it magical. So it’s not a matter of “you did 50%, I did 50%”, or “I did 20% of that song.” It was four people who worked very well together in different formations and we did all cross-fertilize and hybridize quite a bit. There just became a point – and I think it happens to all bands when they grow up and begin to understand what they are, who they are, and what their appeal is -- when you’re beginning the process of making a new record and a sense of what the expectations are creeps in.

That was the point for me, and I think it was for Lol Creme. The best times were when we didn’t know what we were going to get. We just sat down and did it, and an album was just whatever we managed to achieve in that timeframe. There was no sense of, “We need a funny one, a long and complicated one, [and] one that sounds like one of those.” In order words, there were no contrivances and nothing calculated. The whole thing was an audio adventure.

But then it ceased to be that and there was an air of expectancy and anticipation of what the next album should be, because we had become reasonably successful by then. When that began to seep in, the sense that it wasn’t that enjoyable anymore began to seep in alongside it.

BW: It’s been suggested that Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” may have taken a cue from the concept of the Godley/Creme-penned 10cc song “One Night in Paris’ [“Une Nuit a Paris”]. Is that your feeling as well?

KG: I had no idea; someone told us that. I didn’t hear it until about ten years ago. We actually wrote that in France. Let’s say for instance that they were influenced by it -- I’d feel kind of nice about that if we did influence their writing process to create something like “Bohemian Rhapsody”. That’s pretty fucking cool. What I don’t like is that the record company that Queen was on had the balls to release it as a single, whereas ours didn’t.

All we were trying to do was push ourselves as far as we could go in the songwriting process. I forget who said it, but it may have been Graham who said that the original version of “One Night in Paris” lasted the whole side of an album. I don’t remember that, but what it does say is that we were so in charge of our musical destiny at the time --and we proved we could be successful working that way -- that we were allowed to do it. I think a lot of artists at the time who worked for the big labels and were based in London were under a lot more pressure to turn out something a little more commercial.

But we were lucky – we were out in the sticks outside Manchester where people came once in a blue moon to see how we were getting on. We couldn’t e-mail anything or put anything in their Dropbox for them to listen to. People left us alone to crack on and make whatever our music was going to be.

BW: Speaking of the balance of commerce and art, you and Lol had an interesting transitional period between 10cc and the later commercial successes of Godley & Creme when you put out the Consequences triple album. You’ve mentioned in the past that you and Lol Creme were so involved in the making of that album, that by the time you emerged from the process, punk and new wave had become big, and you felt you hadn’t been very aware of what happened in the outside world while you were making the album.

KG: It was an incredible experience to make that record, but we just ended up on the wrong side of history. I think it was partially a reaction to things we’d been bottling up inside ourselves that would never work with 10cc. So when we were suddenly free from the mantle and the expectancies of 10cc, it just all came pouring out in this mad, fuck-off three-album set [at a time] when the mad fuck-off three-album set was not welcome.

But it was great fun to do. We spent probably thousands of pounds of our own money --without realizing it of course-- on something that is still sort of a cult record in a bizarre sort of way, and there is some interesting stuff on there.

It wasn’t meant to be a triple album. We’d invented a device called the Gizmo that strums the guitar strings and makes it sound somewhat like an orchestra, and we’d never had a chance to explore it fully within the context of the band. We were originally going to take six months off and record an album with it to see what it could do, but 10cc was so successful at the time that that wasn’t acceptable to the powers that be. We were either in 10cc or we were not in 10cc. It wasn’t a very grown-up way of looking at things, so we bailed, essentially.

Commercially, it was a disaster – it was such a shame. Nevertheless, it led us somewhere else. Failures are sometimes as valuable as successes. We got to do music for a Benson & Hedges cinema commercial that used a bit of Consequences, so we came out of that project making music for pictures, little knowing that we’d end up making pictures for music a few years down the line. I don’t regret it in the least -- it’s part of one’s experience, really.

BW: As long as you mention the Gizmo/Gizmotron, I wanted to ask you about that as well. I know there were logistical issues with making it work correctly, but nonetheless, there’s quite an illustrious list of artists who recorded with the Gizmotron like Jimmy Page, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Paul McCartney, Cosey Fanni Tutti, and others. Were those artists getting the Gizmotron directly from you, and communicating with you about using it?

KG: Not really – it did come out on the market as the Gizmotron, and they’ve brought it out again now as the Gizmotron 2.0, using better materials and engineering. We don’t own it of course. Over time, all these diverse musicians were dipping into the idea and using it, which was great. It’s something that we did that was exciting, and we actually created something that people used for a time, so it’s part of our legacy. It’s nice to look back and know that people as diverse as Paul McCartney and Siouxsie and the Banshees used it.

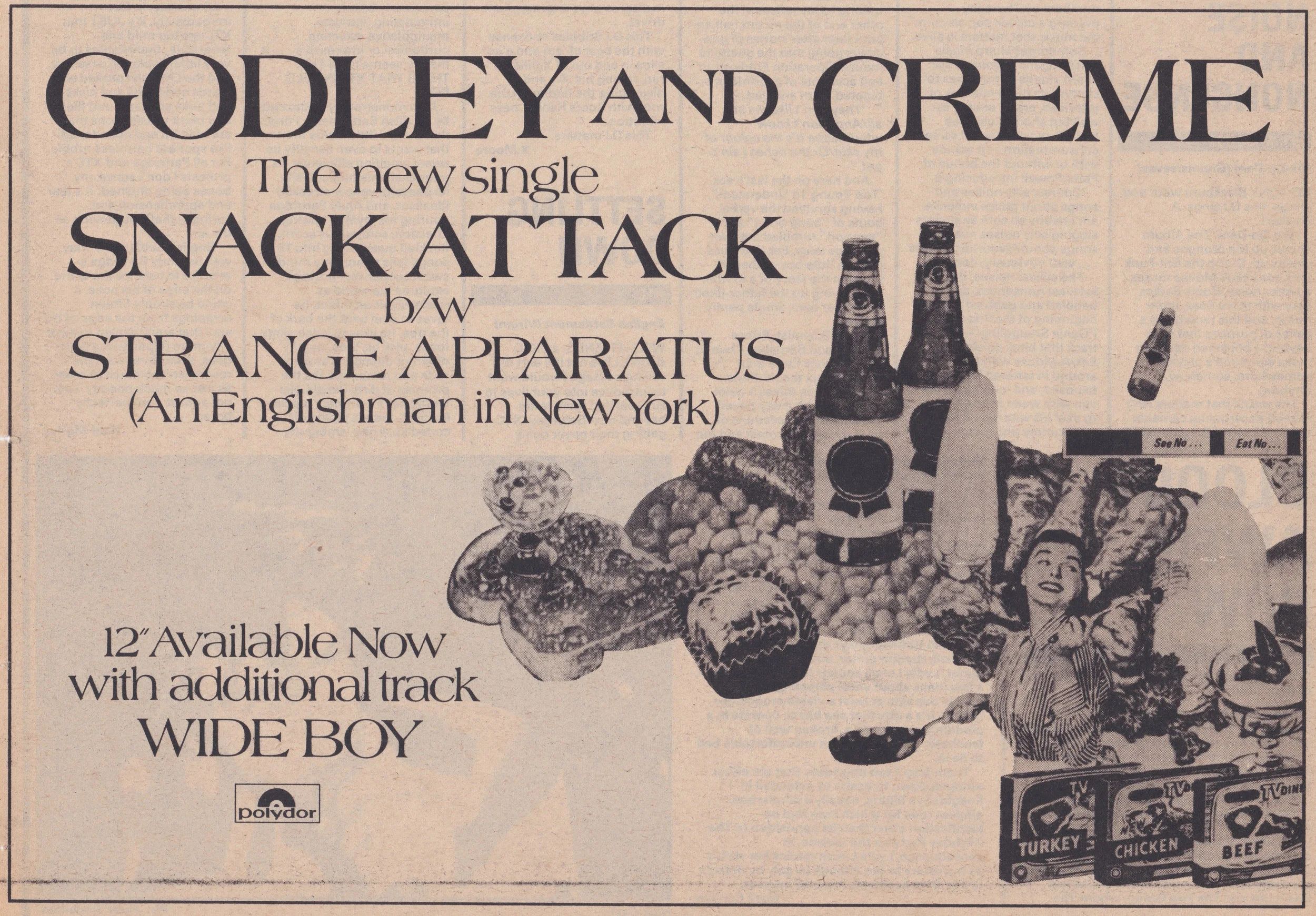

BW: I’ve always been fascinated by the “Wide Boy” video. It’s such a clever and remarkable video, and it’s amazing to watch and realize it comes from the analog world, so it’s not computer graphics that we’re seeing. It appears to be actual posters that you made for that video in order to create the desired effect.

KG: That’s exactly what it was.

BW: It’s so effective, and that must have been something that you had completely thought out before you made it happen.

KG: Oh yeah, and to do that today would be insane. We always felt -- and I still feel -- that if you can think of something and you understand how you want it to look, then it can be done.

That [video] was actually achieved by shooting a scene on video, so at the end of each scene we had a freeze frame that we picked. Then we gave that freeze frame to a photography studio [to] print whatever size photograph we wanted. On another day, we’d come back to the next set, place the photograph within the frame, line up the end of the shot that we’d taken the picture from, and then drive through it or jump through it, or whatever it was that we did. So it was quite a staggered process that happened over a period of days because everything was physically taking place in camera. We didn’t even know it was going to work properly, but people let us do it. It’s astonishing to me, looking back.

The record wasn’t a hit, but the video was surprisingly interesting. I couldn’t imagine doing it today – it’s too involved and probably too expensive to pull off as a promo using today’s technology. That was only the second video we’d made for ourselves, and that was the only technology available. It was analog and very simple and physical -- Stone Age materials. We were brave -- we had an idea and just went for it.

BW: “The Party” is a remarkable track both musically and lyrically. Lyrically, there are several names you mention in the song, and I’ve wondered if those are real people.

KG: It was based on a party that I had at my house, and all the people mentioned in the song are real people. It was written at a time when I’d recently slipped a disc, so I was laid out on my back and had plenty of time to write lyrics.

The Benmen were Ben Kelly and his other half Chrissie Walsh. Ben is an architect and interior designer who designed The Hacienda in Manchester, and Chrissie was a fashion designer. Jon and Wendy are good friends – Jon [W. Prew] is a photographer and Wendy Dagworthy a successful fashion designer at the time, who became head of Fashion at the Royal College of Art. The Targets were Phil Manzanera [Phil Targett-Adams] and his wife. And so on and so on…they’re all real people. We were pastiche-ing a party and the mood of the times.

BW: And you hoped the whole world came to your birthday party.

KG: Yeah, exactly. The whole of my world came.

BW: I’d like to revisit some of the classic music videos that Godley & Creme directed, including the one for Herbie Hancock’s “Rockit”. The video is brilliant, and is especially noteworthy in that it’s pretty unabashedly English, in a sense. It’s not necessarily the environment you’d expect for Herbie Hancock, and yet it works so wonderfully with the music and is such a memorable video. Were you given free reign on what to do with that one?

KG: Pretty much, because if you think about that time, it was very early -- ’83 or something. Video as a medium was in its infancy. Music people – particularly serious music people – didn’t really get it. Nobody really understood what an impact music videos would have on the industry, so they were really just promotional films to show when the artist couldn’t appear on TV.

“Rockit” was unique. I think MTV had already begun to function in the States, but no one really knew what a video was so [labels] came to people who made them, like me and Lol Creme. I think they came to us because we had a musical background and they trusted our thought process. “Rockit” came out of a series of coincidences. I’d seen something on an English news program that featured the work of an artist named Jim Whiting who built these fascinating hydraulic robots. I grabbed the last five minutes of it on video tape because it was really startling and quite disturbing.

Two or three weeks later, “Rockit” arrived with a request to do a video for it, and Jim Whiting’s work just fitted perfectly with this bit of music. There was no red tape-- we didn’t have to submit a treatment or go through the budget. We said “We’ve got an idea,” and they said, “OK -- make it.”

They flew Herbie over to England, and we filmed him playing his keyboards and doing his parts in our office. Then the second day was all the robots. We had a set built to house Jim’s family of creations, then he made some more for the shoot, and off we went. All we knew at that time was that we were filming something interesting, it looked amazing, and it went with the music. We put Herbie’s images on a TV within the set.

It never occurred to us [to ask] if it was too wild, and how people were going to respond. It would be very easy to do now, but back then it was impossible -- or very difficult-- to scratch video tape the way people were scratching vinyl. You can’t just put your hand on video tape and do it backwards and forwards, so we had to transfer the film, running all the footage forwards and running all the footage backwards, editing between the two to get that effect. It was all done in 24 hours of non-stop editing.

At the end of it we played it back and thought, “Oh, fuck – this is nuts. They’re going to kill us!” But the opposite was true -- whereas Consequences was an example of bad timing, the “Rockit” video was an example of good timing. We were in the right place at the right time at the very beginning of an industry that didn’t really know what it was supposed to be doing. We helped to define what it was doing by just following our taste buds, and it won five MTV awards. I think we got more awards that year than Michael Jackson did, so that video was a big step up for us.

BW: On the musical side of things, the Godley and Creme track “Under Your Thumb” is kind of a surprising hit in that it’s a pretty minimalistic track. Is there a particular backstory to why the track is the way it is?

KG: We’d been recording down the road at a great place called Surrey Sound, and we [also] put some of our own money into setting up a little studio at Lol’s house. He had an art room he wasn’t using for art anymore, and so we put the studio in there. He was learning how to operate the desk, and we got a little synth.

We were getting into sequencing and programming at that particular time, and Lol had been up all night coming up with a very fast backing track that he played for me when I showed up at his house the next day. I started subconsciously singing along with it -- as you do -- and came up with the chorus immediately. We just sat down and wrote from that point, and within a couple days we had a song. We recorded it and went to the record company with it. They put it out and it was a hit. It was crazy, because at the time we weren’t concentrating on music as much as we were directing music videos.

We put “Under Your Thumb” out, left it, wished it well, forgot about it, and just got along with what we were doing. I remember we were directing the “Thunder in the Mountains” video for Toya Wilcox, which involved her riding a chariot. We were shooting it on an abandoned airfield somewhere, and someone came running up and said, “You’ve just come in the Top 50 with ‘Under Your Thumb’, and we were flabbergasted. We thought we were directors, and not pop stars anymore. It did really well, but we didn’t have time to do a video for it because we were too busy doing them for other people.

So again, it was one of those unexpected moments that happen throughout your life that aren’t calculated or contrived. There wasn’t a huge amount of push behind the record -- it just seemed to fit, and it worked. It was our first hit on a short run of hits from that point on. We became known as Renaissance Men, and that was pretty cool.

BW: Speaking of being Renaissance Men, you and Lol did a book with pen and ink drawings. Is drawing still a part of your life?

KG: Not so much drawing these days, but I do art. I won’t give it a capital “A”; I’ll give it a small “a”. It’s a different kind of art and it’s purely accidental.

A few years ago I did a music video, and for whatever reason, I couldn’t stay for the final composite of the film, which was a very heavy post-production thing. I had to go home, and I said, “Send it to me over the wire so I can check that everything is how it should be.” By the time I got home, it was there, but the file was corrupted -- it was a complete fucking mess. I was very pissed off and I called the suite and said “Please send it to me again -- it’s broken.” While they were proceeding to send it again, I looked through what they’d sent me, and the film had been ripped apart and reassembled in quite bizarre ways. The imagery --re-appraised as a series of still frames -- was amazing. In other words, the fuck-up had created -- or rather revealed -- art within art. There were hundreds of stills in there that were quite astonishing.

So a little while later, I found a local genius named Dermot Tynan, [who has] a brain that works in the opposite way to mine. He speaks and thinks in code and he made me some software that essentially duplicated the fuck-up. Now, if I make a film that I think will work, I run the film through this process. If I’m lucky, I get some extraordinary results. It’s like doing art, but the only control you have over the process is to choose the size of spanner you throw in the works.

So that’s how I’ve been directing my artistic stills impulses at the moment. I’ve just put a picture into a charity auction for Syrian refugees, and I’m planning an exhibition of this material. That desire to create still images is still there, although I don’t draw much these days. I never did paint – I’m much more into monochrome. [The desire] never went away -- it just came out in a way that seems to belong more in the 21st Century.

BW: Godley and Creme’s “Cry” track and video are both classic, and you revisited the video concept for Elbow’s “Gentle Storm”. It feels like “Cry” pre-figured the Michael Jackson “Black or White” video…

KG: Definitely.

BW: But it’s more poignant in a way, since it’s not just about the visual trick of going from one face to another -- it’s more about the overlapping of different human faces. I’m wondering about the background to that video -- where the idea came from, and how difficult it was to execute.

KG: There are two elements of accident involved in the creation of this. First, we recorded the song. Lol and I were in New York, editing the Synchronicity concert film for The Police. Trevor Horn was also in New York, and we hung out a lot together, drinking a lot of Long Island iced teas. We decided that when we all got back to London we should try working together on some music.

When we reconvened in London, what we originally wanted to do didn’t work out. So Trevor asked if we had anything else. We had the first verse of “Cry”, and had been writing that song for fifteen years. We could never ever get past that first verse for whatever reason. We played it for him and said we couldn’t take it any further. He [thought we should] attack it in a different way, so he brought his sound guys in -- Steve Lipson, J.J. Jeczalik, and his whole team at SARM Studios. They sampled bits, worked with the Synclavier, and created a backing track based on what we’d originally written.

We followed Trevor’s lead on that one, and it was the first time we’d ever really worked with a producer. We just created it in the studio. I had various lyrical ideas, and they’d say, “Try singing this here” and “Try singing this there.” Essentially, it was a patchwork quilt that was eventually assembled into this recording called “Cry”, which turned out really well and better than we’d anticipated.

But then came the moment when we had to make a video for it. By then, Lol wasn’t into performing in videos anymore. We’d done a video for a song called “Wedding Bells”, and he was uncomfortable about that -- he didn’t feel it was very him. So we had to come up with an idea that wasn’t going to challenge us as performers on film. The first idea we came up with was to get two very popular ice skaters called Torvill and Dean to skate to the song. They loved the idea, but we couldn’t get our schedules to work. The faces idea was essentially Plan B.

We thought, “Well what else can we fucking do? It’s not going to be just you and me sat there, singing it for God knows how long -- four minutes or something. It’s the kind of song that everyone can sing, so [we decided to] pick a load of people who could actually sing it -- or mime to it -- that look more interesting than we do. We went through a casting book and picked out a bunch of faces and sent everybody cassettes of the song to learn. We all showed up at the studio one day, and filmed them singing it. We lined them up with the camera so their eyes were approximately in the same position in the frame, and everybody mimed the song.

We thought we could do something interesting with it, but it was only when we got in the edit suite that the true possibilities of what we’d filmed came into being. We were trying different ways of getting from one face to another, and at first we just cut between them. That didn’t work, so then we dissolved between them, and that worked better. But back then, there were very simple tools called wipes which essentially were when you could move a line from one side of the screen to the other, from the top to the bottom, or open a hole in the middle and widen it out in order to go from one picture to another, and then you could put a soft edge on that.

That’s all that’s really going on. We discovered that if you used a wipe that went from the middle outwards, or from the top or bottom of the frame going in the opposite direction, you could -- by moving it at the right speed on the way from one face to another -- create a face that didn’t exist. We thought that was cool, and carried on doing that.

If you watch the film, the first two or three dissolves are very straight -- they’re just full faces mixing to the next full face. But about three or four in, they start to become this weird hybrid where one face becomes a non-existent face on its way to another real face. That’s what made it happen. Plus, a human face -- or a series of human faces -- are always fascinating things to watch anyway.

There was always a sense that it would be black-and-white, and we filmed it in black-and-white. Again, it was just instinct that led us to the right place – we had no idea when we started filming it that it would turn out as interesting as it did, and I think it was the video more than anything else that made “Cry” a hit.

BW: Did anyone connected to Michael Jackson ever contact you later and let you know that they planned on doing a video that was similar to what you did with “Cry”?

KG: No, because what they did wasn’t what we did. It had a similar look, but they used something called morphing, where we were using very basic analog technology to do ours. It was primitive in comparison to what morphing is, which takes one picture and bends it physically to match the incoming picture. We weren’t bending anything – we were just fading in an interesting way from one picture to the next. So what you’re seeing isn’t really there.

BW: What updates or adjustments did you make for the “Gentle Storm” video for Elbow?

KG: It’s exactly the same process, but rather than shoot on 35mm film, we shot on 4K digital video. That was the only difference; I wanted to keep the purity of the original process intact. It was done in exactly the same way with exactly the same spirit.

BW: You did a couple videos with someone I know -- Tim Burgess -- when you directed two memorable videos for the tracks “Forever” (1998) and “A Man Needs To Be Told” (2002).

KG: And both [those] pieces I did with them were physically challenging. In the first video I had Tim crawling along a sheet of glass, and for the second one, I hung the entire band upside down for most of the day, but they’d made the horrendous error of going out for an Indian curry the night before. So that was a long day -- what can I say? But they were wonderful to work with.

If I do videos with people these days -- and even back then -- I tend to give them something to challenge them either mentally or physically, which means I get a an unexpected performance. I like to take people ever so slightly out of their comfort zone. I think maybe I went a little too far with those two pieces, but they turned out well.

BW: This might be a be an obscure one, but I’ve always wondered about the amazing sweaters you’re seen wearing in classic 10cc and Godley and Creme footage and photos.

KG: Sweaters?

BW: I think you’d say “jumper” in the UK. You had one that looked like it had your image on it. Another comes to mind that had a woman’s image on it. Do you have any recollection of those?

KG: Oh yeah, there’s one with my picture on it, and that was made by a London fashion designer called Paul Howie, as was the other one with a woman’s face.

BW: I know you’ve been busy recently with several projects, including new videos that are shown at 10cc shows for CG/06’s “Son of Man” and updated visuals for “I’m Not in Love”. Also, your album Muscle Memory was set to come out last year, but I don’t think it’s come out yet, right?

KG: That’s correct. You’ve probably read in the press over here that there seems to be a problem at Pledge Music. No one really knows what’s going on. I’m told artists haven’t been paid and people aren’t getting what they want. I hate to talk badly of the company because I’ve been working well with them, but there’s something going on, so I’m in the process of looking for alternative ways to release Muscle Memory just in case.

Musically, I’m happy with where I am. I’m ten songs into a twelve-song album. So I’ve got two more to do, and I’m just dealing with the potential mechanisms of release. I think I’ve found a possible alternative, but I don’t want to say what until it’s real. It’s all very exciting, because it’s the first solo album I’ve made. It features many collaborative efforts with other people from all around the world, so it’s been a very absorbing project.

But I’ve been doing lots of other stuff [as well]. I’m now on the board of a video game and technology company called Blue Sock Studios, which is another thing I can apply my thought processes to. I’m doing the art projects I mentioned before, and I’m involved in the creation of a musical show.

I did an acting role, which I’ve never done before. I was asked to play the part of a bogus satanic cult leader in a forthcoming podcast which is coming out in May called The Seventh Daughter. It’s sound only, but I play this rather evil English Alistair Crowley type character, which was a lot of fun to do. I did do some acting previously in a project called Hog Fever, which you might find amusing.

Probably the biggest project on my slate is to direct my first feature film, which is from a screenplay I’ve written called The Gate. It’s written from the perspective of Orson Welles on the last night of his life, looking back on his early years traveling through Ireland as a prospective landscape painter and ending up in Dublin at the Gate Theatre to perform his first professional engagement as an actor. So that’s something that’s very high on my agenda.

BW: Is that film project something that’s been green-lit, or where are you with that process?

KG: I’m amber-lit, if there is such a thing. I’ve written the screenplay, and am finding people who want to work with me on the project. People are liking the screenplay, and we’re just about to join a production team who want to make the film happen. The film hasn’t been green-lit, but there’s very good momentum behind it. Putting a film together is a complex process -- they should give Oscars for getting a film made, let alone making a good one. So I’m about mid-way -- the screenplay took about a year to write, but it was a fascinating experience.

So that’s important to me, as is all the other stuff. I’m just incredibly grateful that I’m still able to work in all these different mediums, and people still want me to do so.

It’s all the same to me -- it’s like I have four taps in front of me, and I can turn any one of them on and the same stuff comes out of the music tap as the visual tap, or the writing tap. It’s all the same basic KG building blocks -- I’m just lucky enough to be able to mold it in a number of different ways.