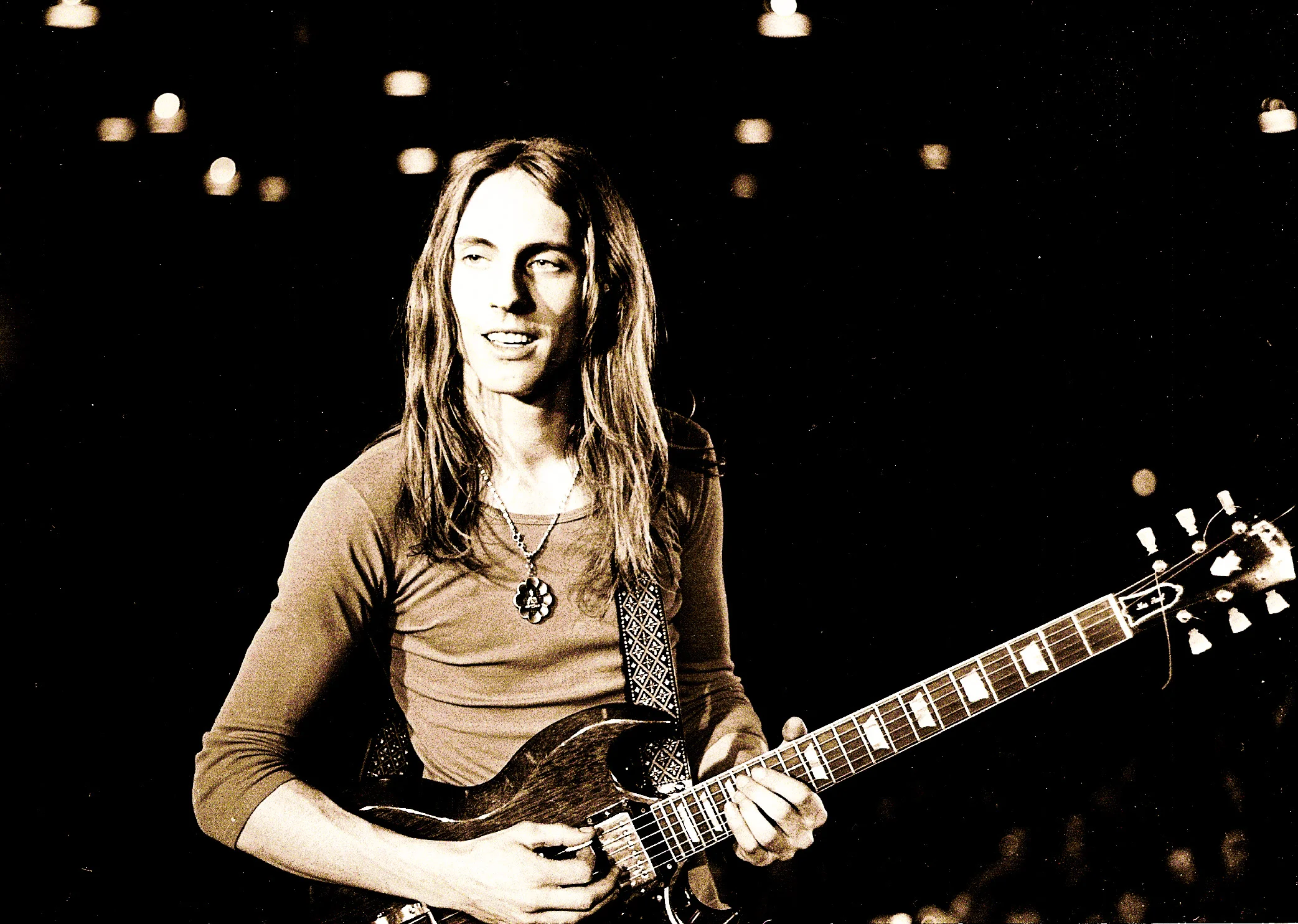

Manuel Göttsching Talks Ash Ra Tempel, Live in Melbourne, Cosmic Jokers, and More

Manuel Göttsching and Ash Ra Tempel are familiar and esteemed names to a global audience interested in experimental music, early electronic music, and so-called Krautrock. The enduring legacy of Ash Ra Tempel has especially been on our minds here at WMF with the stellar 2017 Ash Ra Tempel Experience release, Live in Melbourne. The album features founding and sole consistent member Göttsching, ably supported by Ariel Pink, Shags Chamberlain, and Oren Ambarchi. Recently, Manuel was gracious enough to engage in an illuminating conversation with us about the new album, upcoming shows, classic solo releases, his participation in the fabled Cosmic Jokers sessions, and more. (Part two of our conversation is exclusively dedicated to Live in Melbourne)

Bobby Weirdo: What is Berlin like these days? It must have changed so much over the past decades.

Manuel Göttsching: I don’t know – I’ve lived here all my life. It has changed of course, over the years.

BW: You’ve said before that the first Ash Ra Tempel album in particular was a document rather than a produced piece of music. You wanted to capture the process of the live performance.

MG: For me, music is a live event, and the recording is just something to preserve it. I was never into big studio productions. I did it a few times in my own studio, but basically music is for me a live thing, and that’s the reason that in recent years, I’ve only released live recordings of my performances.

BW: In past interviews - including our own- you've referenced Steve Reich's 6 Pianos and 2 Marimbas as well as Music for 18 Musicians. What is it particularly about Steve Reich’s music that has been an influence on your work? Is it the minimalism, or something else?

MG: It’s minimalism , but in its original and classic way of meaning. I think minimalism today is sometimes a bit misinterpreted. Many young people think minimalism means that not much is happening. You may add a little here and then, and then it might be filed under "minimalism“. But the real idea of minimalism is a very strict formula, reducing something to just a few elements. You take those, and then make the most out of those little elements.

One of my favorites, of course, at the very beginning was Terry Riley, but he was more a soloist. He impressed me with his virtuosity, playing an instrument. He was a perfect keyboard/piano player. He used very little technical equipment – just an electric organ and some tape delays - and he created all these repeated minimalist patterns. It really impressed me and led me to produce my first solo album, Inventions for Electric Guitar [1974], because I thought, “Well, I’m a guitar player, so why not try to make this [music] with electric guitar?"

Steve Reich is for me a great composer, who composes the pieces and stretches them. He studied and was influenced by African rhythms. I like his rhythms and structures of patterns. The thing that really attracted me was that it sounded like electronic music, and in the 1970s, young people were thinking a lot in terms electronic music, playing with synthesizers, and sequencing. Steve Reich was performing music with a classic orchestra, but it sounded completely like electronic music, and I loved it.

BW: The Steve Reich influence on your work seems especially strong on something like E2-E4.

MG: E2-E4 was a longer experience that started with Inventions for Electric Guitar. It wasn’t just a composition; it was a mixed structure of composition and improvisation. I had begun to build my own studio and to work with synthesizers, keyboards, and organs. I collected more instruments and built up my studio, recording every day and night. It was a development over the years from 1974 to 1980. I also performed some of the electronic concerts for a friend back then who was doing curious fashion shows which were more like events. I performed live electronic music three times at those, for about 80 or 90 minutes [each time], so I got used to playing and performing with analog synthesizers, computers, and sequencers. Finally, in 1981, I did just another one of those sessions, and it was really great for one hour. That was E2-E4.

BW: How would you describe the Cosmic Jokers sessions – as a loose association of musicians? I know you already knew the producer and were asked to participate. Was it essentially an experimental improvisation session?

MG: Yes, it was. The idea for the Cosmic Jokers actually started in summer 1972 with the recording of Seven Up with Timothy Leary in Switzerland. Our Records was a small label that was very influential at the time with experimental groups like early Tangerine Dream, Amon Düül, Popul Vuh, and of course Ash Ra Tempel. The recording of the Seven Up album with Timothy Leary was really exciting, and the producer [Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser] decided to create a new label for this release, Kosmische Musik ( Cosmic Music). He wanted to continue producing music in this way – to get various musicians together to play in the studio. We recorded an interesting album about Tarot cards in December 1972 with the Swiss painter (Walter Wegmüller) who painted new Tarot cards. And from the beginning of 1973 we would just meet a few times in the studio, and musicians from various bands would have recording sessions. It was like a big party for several days in the studio, and it was a great experience. We got familiar with the studio and with recording techniques. At the time it wasn’t easy to get into a studio and learn about techniques, and it was comfortable surroundings, playing or not playing. The tapes were running all the time, and it was so fun. After some months, Kaiser edited some tapes, and released it as a series called "The Cosmic Couriers".

BW: You were also spending time with Florian Fricke and CAN during the 1970s.

MG: That was around ’72. I never played with Florian, but was good friends with him. He came to Berlin and was very interested in Ash Ra Tempel’s album Seven Up, so I played him the tapes over and over! I met him again in the late 70s, but there wasn’t that much contact between musicians because Germany was split. The territory of West Berlin was isolated by the Wall, and traveling to and contact with West-Germany was troublesome. I loved CAN in the early 70s, and we performed concerts together in the south of France, so I became friends with them and visited them in the studio in 1976 in Cologne. But everybody was working on their own. What we call the Cold War period meant that everybody was going their own direction. Today, it sounds like everybody was a big family, but actually it wasn’t. We were all very different.

BW: What is your relationship to blues? While your music is so innovative, there are also blues influences, and you’ve cited early Fleetwood Mac and Eric Clapton as influences.

MG: Blues was very important in my musical development. I was trained for many years on classical guitar, and at the age of twelve or thirteen I formed a beat, or rock band with my good friend at school, Hartmut Enke. We started performing covers. I was the singer in the band, and it was just for fun. Very soon, though, it was boring. We explored music, discussed music, and tried to find our own style. We both liked blues, especially the mid-60s British blues like John Mayall & the Blues Breakers, Alexis Korner, and guitar players like Mick Taylor, Peter Green, early Fleetwood Mac, and of course Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck.

So we took the simple structure of blues just as a reference to start to play something or compose some of our own pieces. We went into improvisation and would sometimes use the blues scheme and melodies. Maybe the best example would be Cream, where they would take a blues theme in the beginning of some pieces, go into a long improvisation, and in the end return to the blues. We tried to work on that, and take the blues as a way of learning to compose music.

We worked in Berlin in a place called Beat-Studio, which is where we met the early Tangerine Dream and all the relevant and important Berlin bands were playing, rehearsing, and performing there. The studio was led by a Swiss composer, Thomas Kessler. His compositions were of a very avant-garde and intellectual type of music, but he was an excellent teacher. He taught us how to improvise, to work with music, and to play together in a group. Finally, we just left the blues, and began only with improvisation, which led to the first, completely improvised album. Of course, you hear some elements of blues, but it’s more deconstructing the blues, if you like this term. But I still like blues to this day. It’s a very simple form of composing, and a good start for a young composer if you want to try something on your own.

BW: You’re going to be performing E2-E4 and Ash Ra Tempel material again soon, right?

MG: That’s correct. I will be performing in Hamburg, Germany next year at the Elbphilharmonie. The director Christoph Lieben-Seutter is a big fan, and he invited me to perform a double program. We’ll be playing E2-E4 and the Ash Ra Tempel Experience. It’s scheduled for June 15, 2018 in Hamburg, and we also are hoping to perform in the U.S. next year as well.