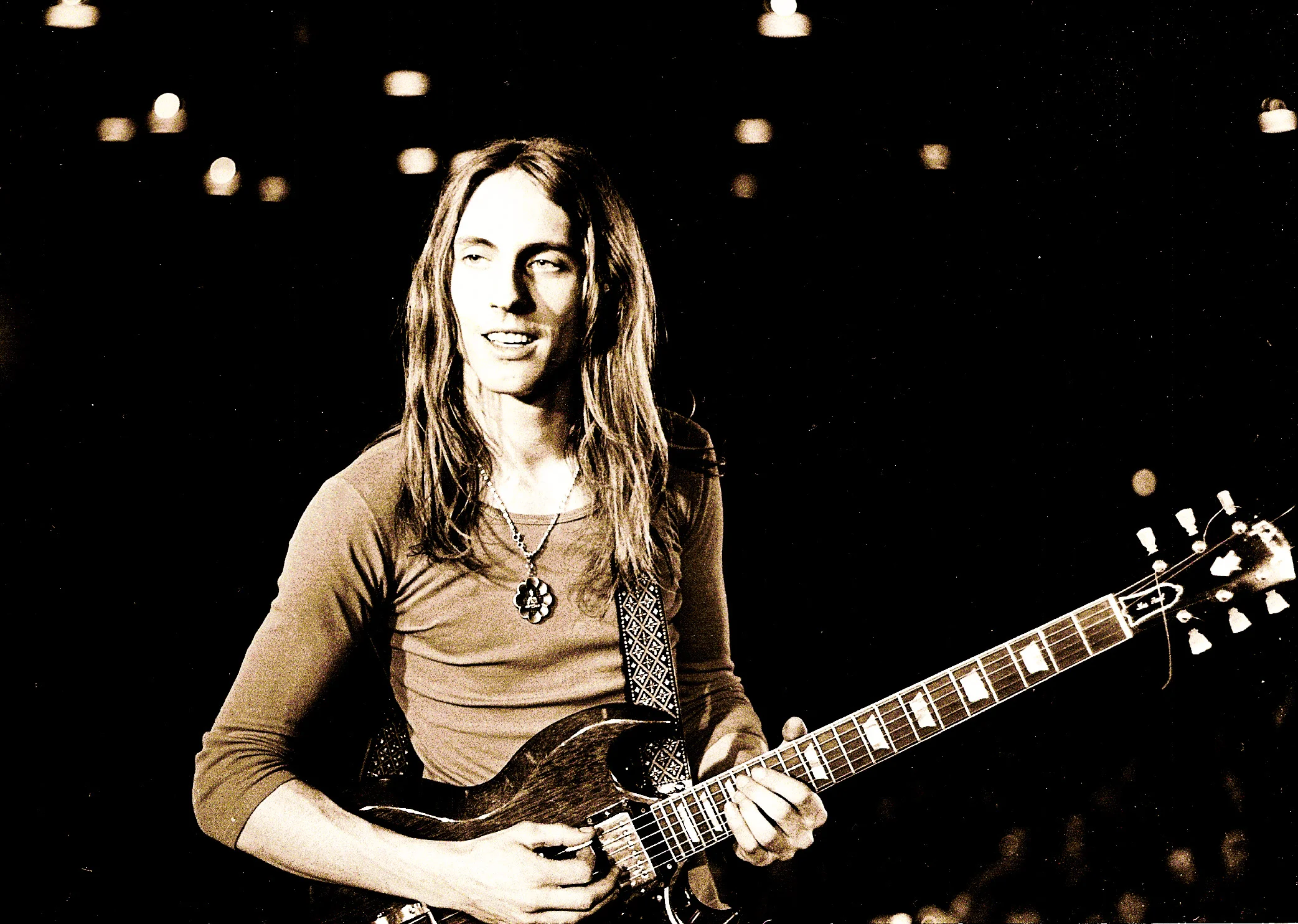

Shags Chamberlain on His Early Influences, Past Projects, New Music, and Record Collecting

Shags Chamberlain and his many talents seem ubiquitous in recent years. His credits include collaborations with Ariel Pink, Weyes Blood, and Ash Ra Tempel's Manuel Göttsching, to name just a few. We jumped at the chance to spend an afternoon with Shags recently at one of his favorite veggie mulita spots and his home studio as we covered his musical and artistic background, his passion for record collecting, past work, and exciting new projects.

Bobby Weirdo: You've mentioned that you’re working on music at home every day these days. Is that music intended for a particular project?

Shags Chamberlain: Yes. The main thing I’m working on is with a Belgian band called Robbing Millions. It’s really, really good music. Basically it’s prog-pop in the sense that Ariel is prog-pop - really catchy pop songs, but with some crazy time signatures and wild melodies. Lucien [Fraipont] is a trained jazz guitarist, so his sense of harmony is really well-developed. He’s very smart and an all-around great musician, but importantly also a great songwriter.

He sought me out to be a producer because he had seen me when Ariel Pink played a show in Brussels. I don’t know why he picked me, but I guess he saw that I have a combination of sophistication and sense of humor, which his music has.

As a general rule, I don’t really work with people who aren’t friends or people I'm not already associated with, and not for any other reason than I just don’t want to be backed up with jobs. L.A. is great for having jobs. There are always records being made, so there’s no shortage of work to do. But it could easily turn out to be not much fun if you overexerted yourself and commited to too much. So I just try to keep it within my circle of friends, which works well, since we’re all making pretty good music. It’s fun, they’re your friends, and that’s how I like to do it.

But we had a connection through Josh da Costa, so he sent music he’d already released. I wasn’t so into it, but asked him to send what we would be working on. He sent about twenty-five demos, and any criticisms I had weren't there with this stuff. The music was so good. I asked for more, and eventually there were fifty incredible songs. We met and worked for the first time in Brussels when I was on tour. We started going through all the songs, writing and arranging, and luckily for me, he was down for any crazy idea I had. We had good camaraderie right off the bat.

That’s been going on since April, and I’ve been over there twice. We’ve picked the songs, got the music sorted out, and he came here for a month recently. I’m finishing it off now and have mixed a lot of it. I think it’s going to be really good.

BW: You told me earlier that you didn’t start playing music until around age 21.

SC: Yes – which was when I had moved to Melbourne and was going to art school. I was coming from a fan perspective, so I taught myself all the Jimi Hendrix songs, all the Pink Floyd songs, all Led Zeppelin, and the Rolling Stones. I would get home from school and basically play guitar until I fell asleep. At some point I got a Hammond organ, and I learned how to play keyboard from what I’d taught myself on guitar. I taught myself all the Small Faces songs, and then I was away.

BW: So you were on track to becoming a visual artist, and then all-of-a-sudden you found a passion for music. What do you think accounts for that?

SC: I think I already had the passion for music, because I was a record collector and a crazy fan. I would read every book there was about whatever I was obsessed with at the time. I even had The Pink Floyd Encyclopedia, so I knew who was living next door to Syd Barrett, and things like that. And I read every book I could find about the Rolling Stones.

I think that’s a great way to approach being a musician. If you’re a fan of [the music] first, you’re expressing the right feelings more than technical teachings.

BW: What kind of visual art were you working on at the time?

SC: I would say it was in the vein of Abstract Expressionism – Color Field paintings. And I worked with watercolor, very cosmic paintings that were pretty transcendental. You could stare at them and get lost in them and be amazed and bewildered.

BW: Do you still paint?

SC: No – I haven’t felt the need to paint for a long time. I get from music what I got from painting. Hopefully [I’ll paint] one day, though. I thought I was born to paint and that I was going to be a painter, but music just took over.

BW: Do you first and foremost consider yourself a keyboardist at this point, or did your guitar and keyboard playing develop simultaneously to the point that you consider yourself both a guitarist and keyboardist?

SC: No, I don’t consider myself a keyboardist at all. I know how to play the keys, but I’m not trained in it in any way. I just know what I’ve worked out myself. I’m just searching for imaginative sounds - crazy sounds that I’ve heard on records - in whatever way I can get them. I’m a delay player, I’m a synthesizer player, a bass player, but mainly I’m just more of an artist who enjoys the production side of it as much as anything. It’s a hard thing to answer, but I’m basically just an artist who is doing music.

BW: You’ve increasingly been doing work in production. You were involved in the production of Drugdealer’s The End of Comedy, for instance, right?

SC: Yes.

BW: How did something like that work. Do you have your producer’s hat on when you’re in that studio?

SC: Yes, I think I do. Whenever I’m in the studio – as a player or whatever I’m there for – I have a producer’s hat on. That’s my natural intuition when it comes to music, and that actually leads back to just being a fan of music. My number one priority musically is probably being a record collector, because I’m constantly searching for stuff I haven’t heard before. So when I’m on tour, it’s exciting to go to a new city every day because there’s a chance that I’ll find music that I’ve never heard before, and many, many people have never heard before.

BW: How did your involvement with Drugdealer come about?

SC: When I first met Mike [Collins] sometime in 2014, Jimi and I were DJing at the Delmont Speakeasy in Venice Beach. Jimi would expand on the DJ concept and bring in a musical element. For instance, he would get Sasha [Desree] from Silk Rhodes, and Mike. Sasha would do a lot of vocal stuff from his loop pedal, and he would merge out of the DJ set into his solo set. And then we would merge back into our DJ set again.

On one particular occasion, I took my Moog. I’d done this already in Australia quite a lot, but I would just jam along to DJ sets on the Moog. I was doing a bit of that, and Mike was there, playing a bit of piano, and we just met and had an amazing night. A whole bunch of people came down, and after the gig we went down to the beach and swam in the middle of the night. We had a great time, and it seemed like Mike and Sasha were going to be my great friends from there on out. We just had a musical crusade from that point on.

So when Mike eventually had all these songs together for the Drugdealer record, I told him to give me the songs to mix. He kept saying he was going to get me to mix it, and that kept going on. Eventually he said he was ready, and wanted it done in a week or two.

So that’s what we did – we started mixing, and I was basically a co-producer from that point on as well. We did the songs, and then he wanted to bring sound effects. I had sound effects records, and he had downloaded stuff as well, and that’s where the extra interludes and atmospheric stuff comes from.

BW: Is your mixing approach the same as your general approach to music – look for a sound, and let that dictate your technique?

SC: I actually have no particular way of approaching a mix – every record is very different. I don’t think I have a trademark. When I mix and produce stuff, there tends to be a timeless quality to it, and I’m not sure what that is. I think maybe because I don’t like to use a lot of reverb, and the way I EQ things it ends up kind of flat and not that bassy. So it seems like [the songs I mix] could be from any era - from the 70s maybe?

But I just approach it in a way to make something the best it can possibly be, by whatever means necessary. And the way I judge that is from being a fan of music. I like to pull in reference tracks, and I think that’s the key for me. Having the reference tracks in the session, and almost needle-dropping. Not only for sound reference, but to keep resetting my ears, because you can really get in your own little mix-hole if you don’t do that. You mix a song and get pretty far in, and you think it’s great. Then you play something from the rest of the world, and realize you’re so far off the mark. Whatever the song is, I try to find a really appropriate reference track to use as a guide. But I also try to find the emotive qualities of the song, and just accentuate that in the mix.

BW: I was speaking with Sophia Brous recently, and she mentioned how you and Ariel Pink are both such fans of music.

SC: He’s a fan, and that’s why he and I hit it off immediately. We first met when he came to Australia in 2006 on one of the first tours with a proper band that was put together. Everyone was great friends and had camaraderie, but he and I in particular would go off on crazy tangents about prog and stuff like that. Ariel would say, “Have you heard of this?” and I’d say, “I have actually. Have you heard of this?” And he’d say, “Yeah! What about this?” We weren’t trying to one-up each other, but just constantly adding to what we know about stuff.

BW: Is there a particular reason you’re not on Dedicated to Bobby Jameson, and touring with the band these days?

SC: Ariel wanted to do this record like he used to do records. He told me before he started recording that he was going to be recording it, and would pull people in here and there where he thought it was necessary. I just thought that was cool, because he’s made every single record in his life – except for one – without me, so it didn’t seem strange to me at all. I’m busy as it is, so there’s plenty for me to do. But I am on it. There are a couple things here and there. I’d walk into the lounge room and he’d say “Hey man. Quick – play this!” I’m not sure exactly what stuck on the final record, but there are little bits and pieces.

As far as the touring band, Ariel wanted to really simplify that as well, so that’s what he did. To play Ariel’s songs, I think you have to be a super fan of Ariel, and everyone in the band doing Pom Pom – and before that – were just super fans, as well as great friends.

BW: So you were familiar with Ariel’s music before you started playing with him?

SC: Oh yeah. Mistletone, which is a record label run by Sophie and Ash Miles, brought Ariel out to Australia. Maybe something like six months before that, the three of us were hanging out and they asked for some cool music to listen to. I had just been thrashing Worn Copy. I told them “this is my shit.” I’d also been listening to an Italian prog band called Le Orme. So I told them they should listen to Le Orme, and Ariel Pink’s Worn Copy. Maybe a couple months after that, they told me they loved Ariel Pink, were going to start a label, and bring him to Australia. I said, “If you do that – I’m in the band”.

So that’s what happened. A band was put together, and initially I wanted to play keys. I had it in my head [that I would], because in Australia I have over thirty synths, so I knew which one was going to be able to do the sounds on the records [from] back then. But they tried two or three bass players, and no one could do the bass, so I said I would do it. It was pretty easy and intuitive for me to do that. They brought him out for an Australian release of House Arrest, and we picked songs from The Doldrums, House Arrest, Worn Copy, Loverboy, and FF. It was cool.

Because we were listening to these old tape recordings, there were sections of songs that just disappeared, because maybe he’d recorded onto some old tape that had been dubbed a million times with Madonna, or Yes, or whatever on them. There were bits cutting out, so we would e-mail him, asking what to play in sections we couldn’t hear, and every time he would say, “Just do your best.”

We’d ask him what the chords were when we couldn’t really hear them. It was very interesting to learn when he got to Australia and we had a rehearsal that he didn't know what an A minor [chord] was, for example, but could whistle or sing any of the parts of the compositions to us. Everything was just in his head. So we can link that back to being a crazy fan of music. He was a crazy fan – he wasn’t a player, but he was an incredible songwriter, and a visionary as well. He just saw it all in his head, and it just took him many years to be able to play those songs and many takes to get them onto records. Now he’s a really good player, too. But the will and vision came first, and the technical aspect came later.

BW: We’ve been talking about record collecting and being a super fan of music. I’ve been to the disco night you DJ with Josh da Costa and Jimi Hey, and disco is certainly a kind of music you’d think has been exhausted. It’s remarkable though, because you play stuff that is so good that many people have never heard before.

SC: That comes from being a crazy collector, going to new cities, digging and digging, and trying to find stuff I’ve never heard before. When we DJ, Josh and I say that we play hits from a parallel dimension. It’s stuff that sounds familiar, but you’ve never heard it before.

That’s one thing I do when I go into record store in a new city. I start by saying that I’m looking for local music between ’78 and ’82 with a drum machine and synths, and maybe a little bit weird. And as soon as you say “drum machine,” that kind of puts them in the ballpark, and they usually come up with something. I’ll check out all the stuff they give me, and when it sounds like what I’m looking for, I’ll say, “Alright - more like that.” And then you find more crazy, weird disco and synth stuff.

BW: How long have you been known to the world as “Shags”?

SC: Since I was nine or ten years old. I wish there were a legendary story, but there’s not. I had a fight with another kid. He called me Shags; I called him Dags. Shags stuck, Dags didn’t, and I remained “Shags”. I didn’t even have long hair then.

BW: You’re very supportive of Sloppy Jane. Did that connection just come about from you seeing the band perform here in L.A.?

SC: Yeah, we’re friends. I met Haley the way you meet anyone, and I think she’s a really interesting person making interesting music. It is kind of as she describes – the Beach Boys crossed with Marilyn Manson. I’m a supporter. I was hoping to help out a little bit mastering some tracks on the EP, but I was too busy at the time. Maybe we’ll work together at some point. I like what she does.

BW: Is Lost Animal an ongoing project?

SC: It is, actually. Jarrod [Quarrell] and I have been talking about doing the third record. He wants to come here, but I might be in in Portugal at that time, so I proposed he come to Portugal and we make a record on the beach.

BW: I love the juxtaposition in that band – Jarrod has a quality that is almost akin to Shaun Ryder or someone like that, where he’s kind of a psychedelic poet against an electronic backdrop. He’s not the vocalist you might expect, and that’s part of what makes the project so effective, I think.

SC: When I try to describe Lost Animal to people, I say that it’s kind of like Lou Reed fronting the Liquid Sky soundtrack.

BW: Right! I mean, the first reference that came to my mind when I heard his vocals on Lost Animal was Bob Dylan.

SC: That’s great you say that, and Jarrod will take that as a compliment. I think Bob Dylan is one of his main influences and one of his heroes. A lot of people don’t get it, and always say something else. If they’re really naïve, they’ll say Nick Cave, and we’re not fans of Nick Cave at all.

BW: You were on Weyes Blood’s Front Row Seat to Earth album and tour. How would you describe your role with that project?

SC: With the record, probably not as involved as we wanted. There wasn’t as much contact as I would have wanted. She wanted me to do synth parts and invent stuff, and I wanted to go in [the studio] and do it, but I actually just ended up doing it from my place. I think it was far less effective, because I like to go in and bounce off of people in the moment. You can expand on or veto an idea a lot quicker if you’re in a session.

From my bedroom I was doing stuff, thinking, “This is cool.” But maybe it wasn’t always in the right direction, and I just had so many ideas, so which one do I spend the time recording? But I did a few songs, and it was cool.

BW: We’ve spoken about your involvement – along with Manuel Göttsching, Ariel Pink and Oren Ambarchi – with the Ash Ra Tempel Experience album, Live in Melbourne. You were already performing with Ariel in Melbourne during that time, right?

SC: Sophia Brous had done the Melbourne International Jazz Festival four times, and turned it into an incredible festival that was more than just a jazz festival. There were amazing acts of all kinds, though they all touched on jazz in some way. She was doing a new festival, and wanted to get Ariel and me down there. So we did a funny kind of duo thing. He picked a bunch of really obscure songs of his – stuff I’d barely heard before.

We basically did an improv Ariel Pink set, which was amazing. In forty minutes while we were in the room waiting to go on stage, we recorded our set on an 8-track, and then went onstage and played on top of the forty-minute cassette that we had just recorded. The crowd response was great, because it was quite a funny set. I guess some people were expecting Ariel Pink pop hits or something, but we did this very absurd set. The jazz and avant-garde people afterwards said, “That was fucking unreal!”